Is technology wearing down the definition of disability?

Earlier this year the American business magazine Fortune put forward an interesting proposition: is the rapid advance of wearable technologies changing the definition of what it means to be disabled?

It’s an interesting premise. In making its case Fortune highlighted several new products, initially designed as assistive technologies but which had been embraced by people without disabilities. These included Lechal haptic footwear which provide step-by-step navigation to visually impaired people through vibrations generated via pods which attach to smart shoes or insole and connect to a smartphone app. The Indian manufacturer created them because the nation is home to 70 million people with visual impairments, but wider applications were soon seized upon as the technology can help plot routes, act as a pacemaker for runners and so on.

To its credit whilst embracing that wider market Lechal is also using it to make its technology more accessible to those that most need it. Every sale to someone without a disability subsidises a sale to some with a visual impairment.

Meanwhile digital disability technology champions AbilityNet point out that new products now come to market with accessibility built-in. The much anticipated and subsequently first adopters’ must-have Apple Watch features magnification and audio prompts as standard features whilst a host of other lifestyle and data apps can be downloaded. So in future your feet and wrist and head might be technologically connected to make the everyday and the extraordinary easier and more fulfilling, perhaps making a tourist trail easier to follow and more meaningful as your watch flags directions, available modes of transport and points of interests.

Apple Watch has accessibility built in.

The possibilities that smart wearables could offer is exciting as the technology gets smaller and, well, smarter. Dave Evans of global IT giant Cisco, who boasts the enviable job title of “Chief Futurist” hinted at the possibilities when addressing London’s 2015 Wearable Technology Show. To demonstrate just how far processing technology has moved on he pointed out that in 1946 £2.6 billion would have bought you the processing power required to operate one of those cheesy talking greeting cards. Yes, that’s two point six billion pounds!

He went on to point out how quickly we are micro-sizing computing, a 32-bit processor – complex and mighty enough to power a smartphone – being launched at just 1.9mm x 2mm and within a few months its size being reduced by 15%. Within ten years we can expect microprocessors to be the size of a red blood cell. The possibilities that then opens are endless with, as Davis puts it, wearables becoming “awareables.”

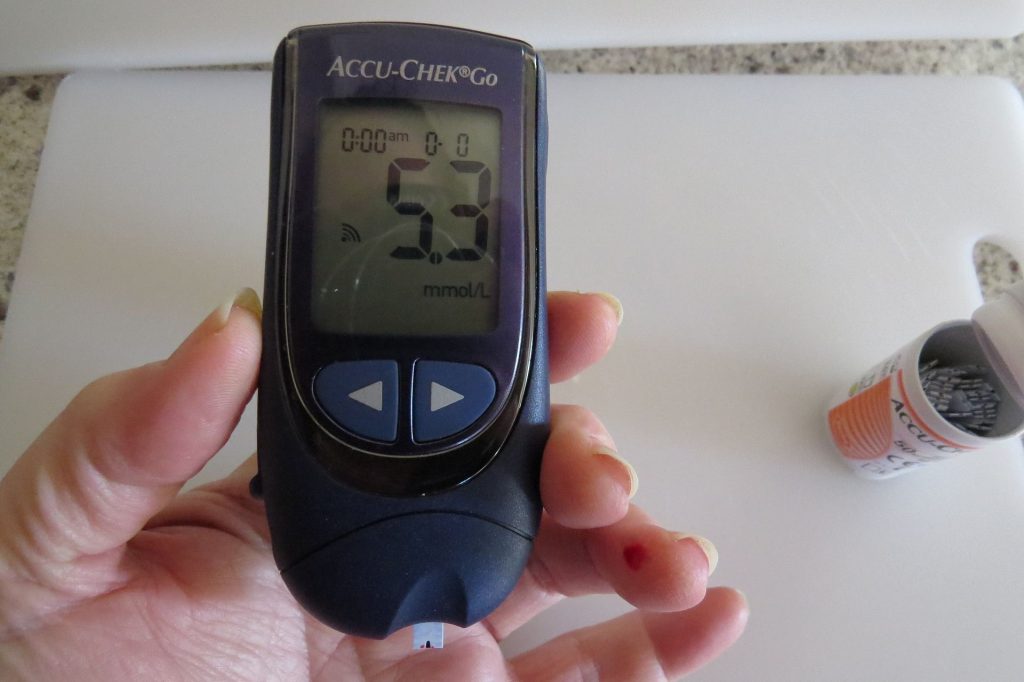

By this he means the technology moves from being react to interactive or pro-active and that takes into account context. As he points out Google has already unveiled a prototype contact lens equipped with microchips and an antenna which can measure glucose levels in the tear ducts. How long before diabetics are using these as medication prompts and prevent hypoglycaemic attacks?

The Scanadu Scout is an existing and relatively cheap device ( dubbed a “tricorder” – it’s developer is a big Star Wars fan!) which measures your vital signs, your blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen levels and temperature. That data can then be shared via social media, text or email via an Android or iPhone app. A natural progression would surely be for an integrated wearable that could constantly monitor and share with your health professionals the data it retrieves?

Strategic Consultancy firm Endeavour Partners points out that wearable health devices are already making inroads. Chairman Michael A.M Davies noted to Information Week that they already exist in the relatively rudimentary form of insulin and cardiac event monitors but argues their real value lies in how they might assist management of chronic conditions.

How long before glucose monitors automatically transmit data to your GP?

He makes a strong case, stating that: “By developing and adopting smart wearables that can collect multiple types of meaningful patient data, (health) providers and payers (in the US, healthcare insurance firms) stand to save money by increasing both patient engagement and preventive care.” Think back to the possibilities a wearable Scanadu Scout type device could offer in collecting, strong and transmitting data which tracks the impact of a chronic condition.

Of course the same technology could also be employed more generally. Rather than nipping to the GP we might all, regardless of our wider health or level of disability, simply slip on a wearable and remotely transmit our blood pressure, glucose levels or whatever else medical data might be required.

Which brings us back to Fortune’s argument. Does it really stack up? The most convincing wearable product it puts forward is the Soundhawk Smart Listening System, a tri-partite product which, you’ll note, is not billed as an hearing aid. Its earpiece element also rejects the trend for discreetness – hide that disability! – being an over and in ear device resembling a Bluetooth headset.

The reason, Drew Dundas, Soundhawk’s chief science officer told Fortune, is that company is “taking a product away from the idea of being a hearing assistive device for people who have a problem to being a performance enhancement for people to improve their quality of life.” In other words it’s about enabling us all to hearing better in environments we might otherwise struggle, regardless of whether we have an aural impairment.

But are wearables really redefining disability? That products are increasingly inclusive as standard is clearly welcome? That assistive technologies might breach mainstream markets through other applications is interesting, but not necessarily ground-breaking when it comes to what it means to be disabled. Surely it is only societal attitudes that can redefine “what it means to be disabled”? It might be that wearables play a part in securing attitudinal shift, but are they alone the answer?